At the functional testing tools workshop, Ward Cunningham devised a scheme. John Dunham, Adam Geras, Naresh Jain, and I elaborated on it. Before I explain the scheme, I have to reveal the context, which is different kinds of tests with different audiences and affordances:

|

|

This is your ordinary xUnit or scripted test. The test is at the top, the program’s in the middle, and the results are at the bottom. In this case, the test has failed, which is why the results are red.

The scribbly lines for both test and results indicate that they’re written in a language hateful to a non-technician (like a product owner or end user). But you’d never expect to show such a person failing results, so who cares?

|

|

|

Here’s the same test, passing. The output is just a binary signal (perhaps a green bar in an IDE, perhaps a printed period from an xUnit TextRunner). A product owner shouldn’t care what it looks like. If she trusts you, she’ll believe you when you say all the tests pass. If she doesn’t, why should she believe a little green bar?

|

|

|

Here’s a representation of a Fit test. Both the input and output are in a form pleasing to a non-technician. But, really, having the pleasant-looking results isn’t worth much. It makes for a good demo when showing off the tool, but does a product owner really care to see output that’s the input colored green? It conveys no more information than a green bar and depends on trust in exactly the same way. (James Shore made this point well at the workshop.)

|

|

|

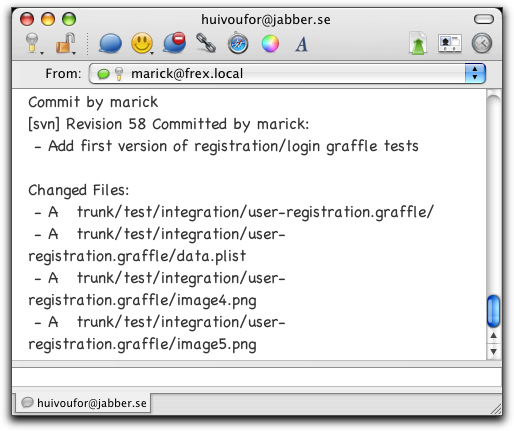

Here’s one of my graphical tests. The input is in a form pleasing to a non-technician. In this case, the test is failing. The output is the same sort of gobbledegook you get from xUnit (because the test is run by xUnit). Again, the non-technician would never see it.

|

|

|

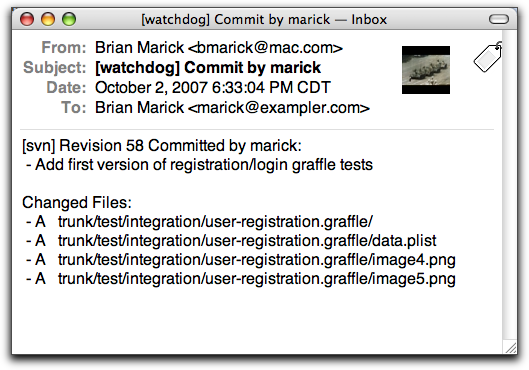

Here’s the same test, passing. My test framework doesn’t make pretty results, because I don’t think they have value worth the trouble.

|

|

|

Here is one of Ward’s “swimlane” tests. The test input (written in PHP) would be unappealing to non-technicians, but they never see it. This test fails, and so it produces nothing a non-technician would want to see.

|

|

|

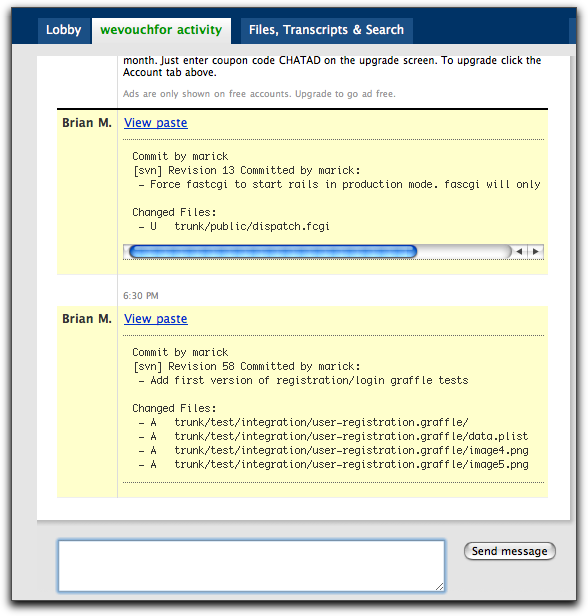

Here’s the passing test. The output is a graphical representation of how the program just executed. It is both understandable (after some explanation) and explorable (because there are links you can click that take you to other interesting places behind the curtain.)

|

As when I first encountered wikis, I missed the point of Ward’s newest thing. I didn’t think swimlane tests had anything to do with what I’m interested in: the use of tests and examples as tools for thinking about a piece of what the product owner wants with results that help the programmers. With swimlane tests, the product owner is going to be mostly reactive, saying “these test results are not what I had in mind”.

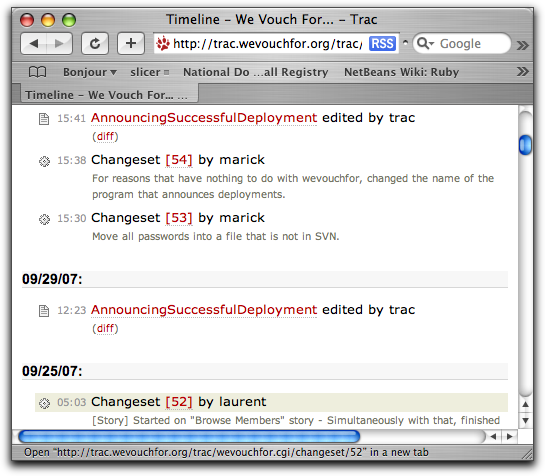

What I missed is that Ward’s focus wasn’t on driving programming but on making the system more visible to its users. They were written for the Eclipse Foundation. It wants to be maximally transparent, and the swimlane tests are documentation to help the users understand how the Foundation’s process works along with assurance that it really does work as documented.

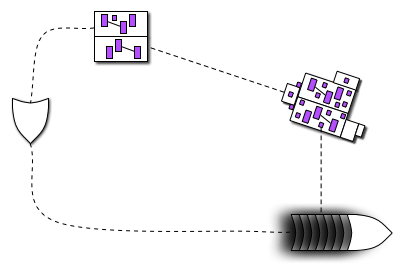

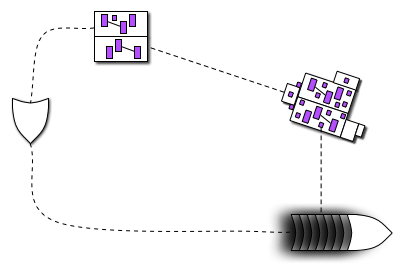

What Ward noticed is that his output might fit together nicely with my input. Like this:

Here, the product owner begins with an executable graphical example  of what she wants. The programmers produce code

of what she wants. The programmers produce code  from it. As a user runs

from it. As a user runs  that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures

that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures  that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples

that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples  .

.

The point of all of this? It’s a socio-technical trick that might entice users to collaborate in application development the way wikis entice readers to collaborate in the creation of, say, an encyclopedia. It’s a way to make it easier for markets to really be conversations. John Dunham dubbed this “crowdware”.

It won’t be quite as smooth as editing a wiki. First, as Naresh pointed out, the users will be pointing at pictures of a tool in use, and they will likely talk about the product at that level of detail. To produce useful driving examples (and software!), talk will have to be shifted to a discussion of activities to be performed and even goals to be accomplished. The history of software design has shown that we humans aren’t fantastically good at that. Adding more unskilled people to the mix just seems like a recipe for disasterware.

Wikis seemed crazy too, though, so what the heck.

Laurent Bossavit and I are working on a site. Once it reaches the minimal features release, I’ll add some crowdware features.

of what she wants. The programmers produce code

of what she wants. The programmers produce code  from it. As a user runs

from it. As a user runs  that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures

that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures  that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples

that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples