Latour 2: ANT and the building of the social

A transcript of an OOPSLA talk: Table of contents

Why does Actor-Network Theory (ANT) care so much about things? Latour explains in terms of baboons. Baboons usually have a pretty good life. They don’t have to spend a whole lot of time looking for food, but they do need protection from predators. That means they need to live in packs to survive. How do they keep the packs functioning well? In the words of the Agile Manifesto, they spend a lot of time attending to individuals and interactions. In fact, they spend all their free time attending to individuals and interactions. As a result, they have no time to write software.

We humans have a trick: we substitute things for social forces. Latour uses the example of policemen. Let’s say that society has decided that people should drive slowly down a particular stretch of road. People being what they are, sometimes some of them will want to drive fast instead. One way to prevent that is to station a policeman by the side of the road. That person exerts a social force that will cause people to slow down.

But then we’d be like the baboon: devoting a lot of time to maintaining group norms. Unlike the baboons, though, we have an alternative:

In the US, we call these “speed bumps.” In other parts of the world, they’re called “sleeping policemen.” (The model pictured is a Rediweld Sitecop sleeping policeman.)

Through a different mechanism, the sleeping policeman has the same social effect as a human policeman: slower cars and an environment matching collective preferences.

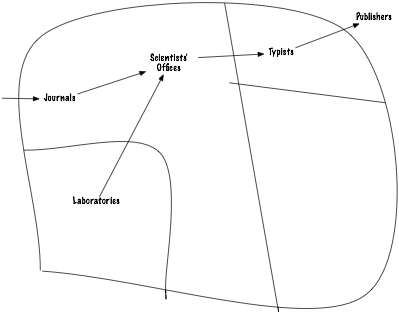

We can take this a step further. Consider neighborhoods. Many sociologists might explain the existence of neighborhoods by appealing to powerful abstract forces like power, class, or racism. An ANT explanation, by contrast, might start with speed bumps.

Consider a car as an “actor” that can affect—push on, act as a force upon—other actors, specifically children. Speeding cars are a danger to children, and they affect their behavior. Children aren’t allowed to play near streets where cars travel fast.

Now suppose speed bumps are put up across those streets. The speed bumps mediate or “translate” the effect of cars on children. The cars become less dangerous. Parents (another set of actors) are more likely to allow children to play outside. As many parents know, children who are playing together outside soon invade houses in packs. Parents come to know the nearby children. And, inevitably, they come to know those childrens’ parents. They begin trading favors like driving children around. They become neighborly.

Now, speed bumps by themselves don’t create a neighborhood, but there are lots of other physical objects that have similar effects, and they keep having these effects, day in and day out. The continual recurrence (”circulation”) of all these forces, all these actors affecting other actors, is (according to ANT) a sufficient explanation for the “assembly” of a neighborhood. We don’t need to bring abstractions like power into the equation.

Does that make neighborhoods somehow less real than cars? (Is ANT purely materialist?) To Latour, neighborhoods are as real as cars if the people in the story talk about them that way. For example, the city council in my town would, if you asked them, say my neighborhood is real. Some time ago, the city wanted to replace our antique street lamps with ugly modern street lamps. The neighborhood pushed back and got more expensive street lamps that fit better with our lovely old brick streets and old trees. To the city council and the people reading about the brouhaha in the newspaper, the neighborhood was an actor that changed things. To Latour, it would be arrogant for an analyst on the outside to tell us that our neighborhood isn’t really real. ANT comes with a respect for the ontology of the people doing the work; that is, it assumes they’re pretty savvy about what things exist in their world.

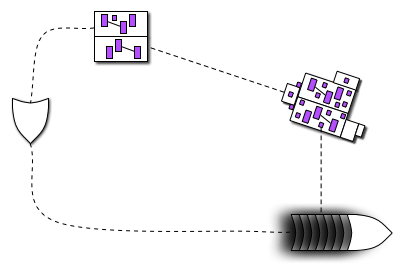

of what she wants. The programmers produce code

of what she wants. The programmers produce code  from it. As a user runs

from it. As a user runs  that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures

that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures  that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples

that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples