I’ve been working through Growing Object-Oriented Software (henceforth #goos), translating it into Ruby. An annoyingly high percentage of my time has been spent messing with the end-to-end tests. Part of that is due to a cavalcade of incompatibilities that made me fake out an XMPP server within the same process as the app-under-test (named the Auction Sniper), the Swing GUI thread, and the GUI scraper. Threading hell.

But part of it is not. Part of it is because end-to-end tests just are awkward and fragile (which #goos is careful to point out). If such tests are worth it, it’s because some combination of these sources of value outweighs their cost:

-

They help clarify everyone’s understanding of the problem to be solved.

-

Trying to make the tests run fast, be less fragile, be easier to debug in the case of failure, etc. makes the app’s overall design better.

-

They detect incorrect changes (that is, changes in behavior that were not intended, as distinct from ones you did intend that will require the test to be changed to make it an example of the newly-correct behavior).

-

They provide a cadence to the programming, helping to break it up into nicely-sized chunks.

In working through #goos so far (chapter 16), the end-to-end tests have not found any bugs, so zero value there. I realized last night, though, that what most bugged me about them is that they made my programming “ragged”–that is, I kept microtesting away, changing classes, being happy, but when I popped up to run the end-to-end test I was working on, it or another one would break in a way that did not feel helpful. (However, I should note that it’s a different thing to try to mimic someone else’s solution than to conjure up your own, so some of the jerkiness is just inherent to learning from a book.)

I think part of the problem is the style of the tests. Here’s one of them, written with Cucumber:

Scenario: Sniper makes a higher bid, but loses

Given the sniper has joined an ongoing auction

When the auction reports another bidder has bid 1000 (and that the next increment is 98)

Then the sniper shows that it's bidding 1098 to top the previous price

And the auction receives a bid of 1098 from the sniper

When the auction closes

Then the sniper shows that it's lost the auction

This test describes all the outwardly-observable behavior of the Sniper over time. Most importantly, at each point, it talks about two interfaces: the XMPP interface and the GUI. During coding, I found that context switching unsettling (possibly because I have an uncommonly bad short- and medium-term memory for a programmer). Worse, I don’t believe this style of test really helps to clarify the problem to be solved. There are two issues: what the Sniper does (bid in an auction) and what it shows (information about the known state of the auction). They can be talked about separately.

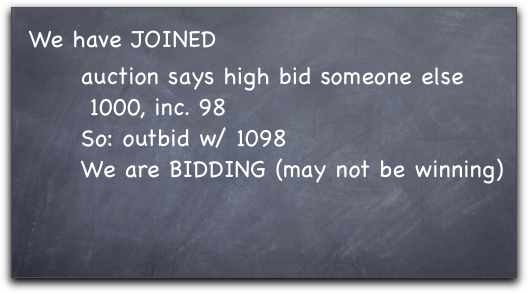

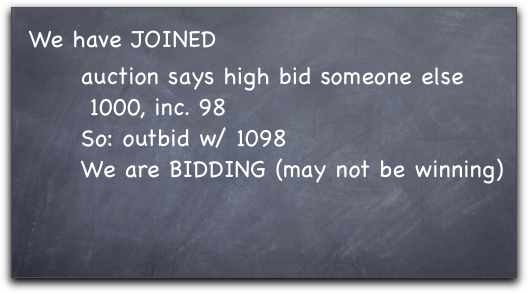

What the Sniper does is most clearly described by a state diagram (as on p. 85) or state table. A state diagram may not be the right thing to show a non-technical product owner, but the idea of the “state of the auction” is not conceptually very foreign (indeed, the imaginary product owner has asked for it to be shown in the user interface). So we could write something like this on a blackboard:

Just as in #goos, this is enough to get us started. We have an example of a single state transition, so let’s implement it! The blackboard text can be written down in whatever test format suits your fancy: Fit table, Cucumber text, programming language text, etc.

Where do we stand?

At this point, the single Cucumber test I showed above is breaking into at least three tests: the one on the blackboard, a similar one for the BIDDING to LOSING transition, and something as yet undescribed for the GUI. Two advantages to that: first, a correct change to the code should only break one of the tests. That breakage can’t be harder to figure out than breaking the single, more complicated test. Second, and maybe it’s just me, but I feel better getting triumphantly to the end of a medium-sized test than I do getting partway through a bigger end-to-end one.

The test on the blackboard is still a business-facing test; it’s written in the language of the business, not the language of the implementation, and it’s talking about the application, not pieces of it.

Here’s one implementation of the blackboard test. I’ve written it in my normal Ruby microtesting style because that shows more of the mechanism.

context “pending state“ do

setup do

start_app_at(AuctionSnapshot.new(:state => PENDING))

end

should “respond to a new price by counter-bidding the minimum amount“ do

during {

@app.receive_auction_event(AuctionEvent.price(:price => 1000,

:increment => 98,

:bidder => “someone else“))

}.behold! {

@transport_translator.should_receive(:bid).once.with(1098)

@anyone_who_cares.should_receive_notification(STATE_CHANGE).at_least.once.

with(AuctionSnapshot.new(:state => BIDDING,

:last_price => 1000,

:last_bid => 1098))

}

end

end

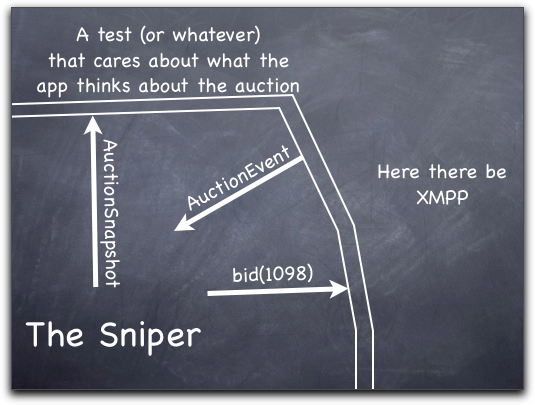

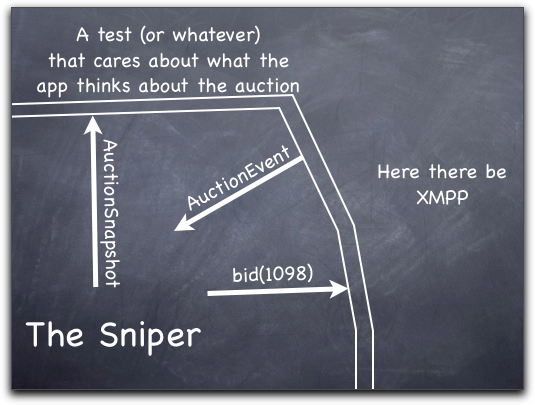

Here’s a picture of that test in action. It is not end-to-end because it doesn’t test the translation to-and-from XMPP.

In order to check that the Sniper has the right internal representation of what’s going on in the auction, I have it fling out (via the Observer or Publish/Subscribe pattern) information about that. That would seem to be an encapsulation violation, but this is only the information that we’ve determined (at the blackboard, above) to be relevant in/to the world outside the app. So it’s not like exposing whether internal data is stored in a dictionary, list, array, or tree.

At this point, I’d build the code that passed this test and others like it in the normal #goos outside-in style. Then I’d microtest the translation layer into existence. And then I’d do an end-to-end test, but I’d do it manually. (Gasp!) That would involve building much the same fake auction server as in #goos, but with some sort of rudimentary user interface that’d let me send appropriately formatted XMPP to the Sniper. (Over the course of the project, this would grow into a more capable tool for manual exploratory testing.)

So the test would mean starting the XMPP server, starting the fake auction and having it log into the server, starting the Sniper, checking that the fake auction got a JOIN request, and sending back a PRICE event. This is just to see the individual pieces fitting together. Specifically:

-

Can the translation layer receive real XMPP messages?

-

Does it hand the Sniper what it expects?

-

Does the outgoing translation layer/object really translate into XMPP?

The final question–is the XMPP message’s payload in the right format for the auction server?–can’t really be tested until we have a real auction server to hook up to. As discussed in #goos, those servers aren’t readily available, which is why the book uses fake ones. So, in a real sense, my strategy is the same as #goos’s: test as end-to-end as you reasonably can and plug in fakes for the ends (or middle pieces) that are too hard to reach. We just have a different interpretation of “reasonably can” and “too hard to reach”.

Having done that for the first test, would I do it again for the BIDDING to LOSING transition test? Well, yeah, probably, just to see a two-step transition. But by the time I finished all the transitions, I suspect code to pass the next transition test would be so unlikely to affect integration of interfaces that I wouldn’t bother.

Moreover, having finished the Nth transition test, I would only exercise what I’d changed. I would not (not, not, not!) run all the previous tests as if I were a slow and error-prone automated test suite. (Most likely, though, I’d try to vary my manual test, making it different from both the transition test that prompted the code changes and from previous manual tests. Adding easy variety to tests can both help you stumble across bugs and–more importantly–make you realize new things about the problem you’re trying to solve and the product you’re trying to build.)

What about real automated end-to-end tests?

I’d let reality (like the reality of missed bugs or tests hard to do manually) force me to add end-to-end tests of the #goos sort, but I would probably never have anywhere near the number of end-to-end scenario/workflow tests that #goos recommends (as of chapter 16). While I think workflows are a nice way of fleshing out a story or feature, a good way to start generating tests, and a dandy conversation tool, none of those things require automation.

I could do any number of my state-transition tests, making the Sniper ever more competent at dealing with auctions, but I’d probably get to the GUI at about the same time as #goos.

What do we know of the GUI? We know it has to faithfully display the externally-relevant known state of the auction. That is, it has to subscribe to what the Sniper already publishes. I imagine I’d have the same microtests and implementation as #goos (except for having the Swing TableModel subscribe instead of being called directly).

Having developed the TableModel to match my tests, I’d still have to check whether it matches the real Swing implementation. I’d do that manually until I was dragged kicking and screaming into using some GUI scraping tool to automate it.

How do I feel?

Nervous. #goos has not changed my opinion about end-to-end tests. But its authors are smarter and more experienced than I am. So why do they love–or at least accept–end-to-end tests while I fear and avoid them?