Complete table of contents

At OOPSLA in Montreal, I gave an invited talk on Actor-Network Theory (ANT), a style of observation and description that’s most associated with the French philosopher/sociologist Bruno Latour. I told some stories about how I use ANT in my work. I also said some hotheaded things about its relevance for some problems I see with Agile. Because blog posts should be short, I’m going to blog this talk in pieces. Here’s the first.

(This first bit is something of a retread for those who’ve been reading my blog since 2003.)

I’m a consultant. I drop into projects for about a week. I work with the people on the project—pairing, testing, whatever. Along the way, I’m supposed to notice things they don’t see and make suggestions they haven’t already tried, all with the aim of helping them get better at building software.

A tough job: projects are complicated, with lots of moving parts. It’s terribly easy as a consultant to see only the things you’re used to seeing. Worse: it’s easy to see things that aren’t there, just because they’re the things you’re best at seeing.

So a consultant needs mental tricks to kick himself out of ruts and habits. I use ANT as such a trick.

An example: the role of testing in Agile projects

One thing ANT people do is pay attention to things and how they move around.

In the mid-to-late 70’s, Bruno Latour—a philosopher who knew little English and less biochemistry—arrived at the Salk Institute in San Diego, California. Not only did he know little about the content of the work they did there, he deliberately tried to forget what he did know. He wanted to be like an anthropologist visiting some completely foreign tribe with a completely different culture.

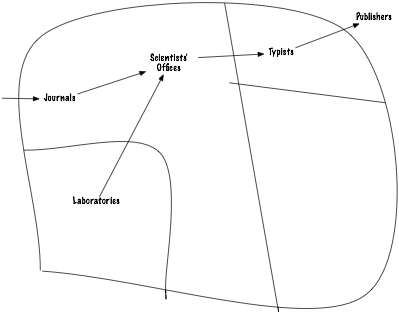

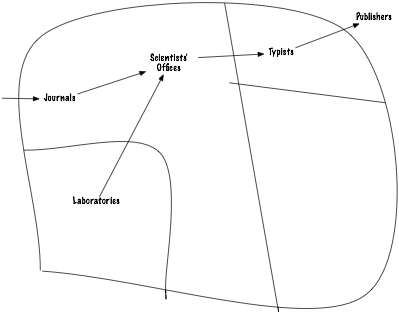

As you might expect, some of his observations were odd. For example, he saw that there was one place in the laboratory where, at periodic intervals, bound sheaves of paper called “journals” were delivered.

At other places, people called “technicians” tended expensive and balky machines whose purpose seemed to be to make marks on paper (line drawings, blotchy pictures, lists of numbers, and the like). These two sets of paper were delivered to a third place, the “offices” of the “scientists”. The scientists put the two types of paper—journals and “experimental results”—next to each other and compared them. As (and after) doing so, they would write things on new pieces of paper, which they would deliver to a place inhabited by “typists”, who would “type them up” (put them in a tidier form), then send them out the door to “publishers” who would, in due course, bind them up together with other “papers” and deliver the resulting journals to… still more laboratories.

To Latour, it seemed the laboratory was a factory for turning paper into more paper.

Now, Karl Popper, likely the most influential philosopher of science, would describe all of what Latour saw as an epiphenomenon, not what science is really about. What science is really about is this:

-

A theoretician comes up with a theory. Oddly, the examples always seem to use really great theoreticians, the ones you’ve all heard of.

-

Someone—maybe the great theoretician, maybe someone else—makes predictions from that theory: in situation X, the world should do thing Y.

-

An experimenter—who you quite often won’t have heard of—will create situation X and observe whether the world does thing Y.

-

If the world does not, the great theoretician has to discard the theory and try again.

-

If the world does do Y, that does not confirm the theory. No number of confirmed predictions logically proves that a theory is true. If, however, the theory passes a sufficient number of challenging tests, scientists are justified in accepting it and using it in their own work.

Popper’s opinion matters to me because some software testers make explicit analogies between Popper’s view of science and testing:

-

The programmer is like a theoretician, proposing a theory like “for any input X typed into this text box, the program will calculate f(X).”

-

The tester turns that into a prediction. “So the program should calculate f(X) if the input is one of those things we call a SQL injection attack.”

-

The tester sets up the experiment, tries a SQL injection attack.

-

If the program doesn’t work as predicted, the programmer has to go back and try again. The tester gets a little thrill, because it really is fun to break programs.

-

If the program passes the test, it may still not be correct—no number of passed tests suffices to prove the program is bug-free. But if it passes a sufficient number of challenging tests, managers are justified in releasing it into the world.

The problem is the effect on an Agile team. At the time I was thinking about this (around 2002), there was lots of tension between testers and Agile proponents. Unwise things were said on both sides. Against that backdrop, the testers’ normal drive-by defacements of the programmers’ programs—and the programmers’ egos—wasn’t contributing to the unity of effort I believe is so important on Agile teams. One could say the programmers should be more egoless, but I’m more inclined to work with the grain of human nature than against it.

Popperian science seemed to be the wrong metaphor. (Besides, having read people like Feyerabend and Lakatos, I was pretty skeptical that Popperian science had anything much to do with how real scientists came to accept theories.)

At some point, a detail of Latour’s book describing his Salk experience (Laboratory Life, with Steven Woolgar) came to me. During the process of turning paper into more paper, scientists would hand out “drafts” to other scientists. They’d then get together to discuss the drafts. The conversation would have this tone:

There’s a good chance that Morin is going to be one of the reviewers of this, and you know how she is about antibiotic treatment. If you want this to get past her, you’ll need to strengthen this justification here.

or

I can help you with SAS, make the statistical analysis more solid.

or

If you included the results of assay X, more people would be interested. I can lend you my technician.

The effect is one of people anticipating what dangers the paper will face when it ventures into the world, and making suggestions about how it might be muscled up to survive them. Although I don’t think I realized it at the time, this is the style of paper reviewing that Richard P. Gabriel had imported from the creative writing community into the design patterns community. (See his Writers’ Workshops and the Work of Making Things.)

This, I realized, was a way of having testers’ skills contribute both to the product and also to the team’s feeling of unity of effort. So I began using this new metaphor in my consulting. The particular suggestions I make depend on the team. I might nudge the testers into the role of supporting the (typically overworked) product owner. They could help her talk more more precisely and comprehensively about what she wants. They could then turn that clearer description into tests that programmers could use in the familiar test-first way. Or I might nudge them into the role of teaching the programmers about the domain, one test at a time. (This affects the kinds of tests you write and the order in which you use them.) And so on.

I think this style of thinking about testing is now pretty common in the Agile world. It probably would have happened without me—I’m by no means the only person to think along those lines. That’s not the point: the point is that I probably would not have thought of it had I not absorbed a bit of Latour’s way of looking at things.

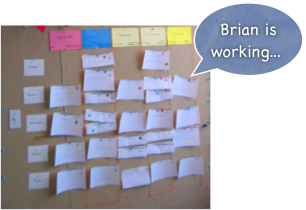

A while back, I was thinking along these lines when I realized that if the stories are so important to the project, they ought to be the ones speaking in the standup. I imagined a story card saying, “Brian’s going to keep working on me today, but he’s having trouble. He could use the help of someone who knows Hibernate.”

A while back, I was thinking along these lines when I realized that if the stories are so important to the project, they ought to be the ones speaking in the standup. I imagined a story card saying, “Brian’s going to keep working on me today, but he’s having trouble. He could use the help of someone who knows Hibernate.” Now, I never had the nerve to actually suggest that team members ought to hold the story cards like little mouths, open and close them, and pretend it was the stories talking, but while I was preparing for this talk, I had another thought. Yes, the stories can’t talk, but there’s no reason not to structure the standup around them. Instead of going around the people, you can step through all the stories in play. For each, someone can say what happened to that story yesterday, what’s to be done on it today, and whether there are any risks to its completion.

Now, I never had the nerve to actually suggest that team members ought to hold the story cards like little mouths, open and close them, and pretend it was the stories talking, but while I was preparing for this talk, I had another thought. Yes, the stories can’t talk, but there’s no reason not to structure the standup around them. Instead of going around the people, you can step through all the stories in play. For each, someone can say what happened to that story yesterday, what’s to be done on it today, and whether there are any risks to its completion.

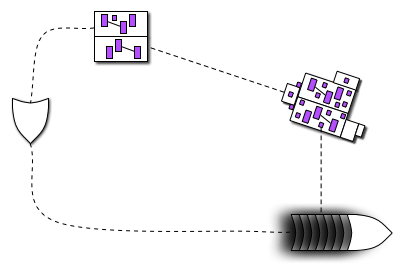

of what she wants. The programmers produce code

of what she wants. The programmers produce code  from it. As a user runs

from it. As a user runs  that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures

that code, she can at any moment get a bundle of pictures  that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples

that she can point at during a conversation with the producer and other users. That might lead to some new driving examples