Exploration Through Example

Example-driven development, Agile testing, context-driven testing, Agile programming, Ruby, and other things of interest to Brian Marick

| 191.8 | ⇒ | 167.2 | ⇒ | 186.2 | 183.6 | 184.0 | 183.2 | 184.6 |

Exploration Through ExampleExample-driven development, Agile testing, context-driven testing, Agile programming, Ruby, and other things of interest to Brian Marick

|

Fri, 23 Feb 2007Need product directors for London workshop I'll be in London at the end of March. While I'm there, I'd like to have a little workshop for Scrum product owners, XP Customers, and product directors. These are the people who:

I believe those people have the hardest job on Agile projects. They are also the most likely to be isolated: programmers talk with programmers, testers talk with testers, but these people often have no peers to talk to. In this workshop, I want to gather up to 20 of these people and have them teach each other about problems they've solved. We'll use a particular format (described below) that's proven effective for such things.The dates will be on the 29th and 30th of March (total time one and a half days). There'll be some fee to cover expenses (not exceeding £50). We'll select people on the basis of one-page statements of the problem they had and solved. People who are programmers, testers, and project managers can also come, but product directors will have precedence. I'm sending this note to gauge interest and decide whether to book the room (at the Royal Statistical Society, 12 Errol Street, close to the Barbican centre). Please forward it on to likely candidates. I'll decide on March 2, based on how many product director types send me mail saying they're interested. Questions to me: marick@exampler.com. ==========The format.

Depending on interest, we may also have lightning talks or breakout sessions. This format is a variant of the one used in the Los Altos Workshop on Software Testing.

## Posted at 08:39 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Tue, 20 Feb 2007Pictures of team rooms, walls, etc. Here are three sites that use pictures to show what Agile artifacts and physical environments look like.

Bill

Wake

## Posted at 07:20 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Sun, 18 Feb 2007While I'm talking about metaphors...

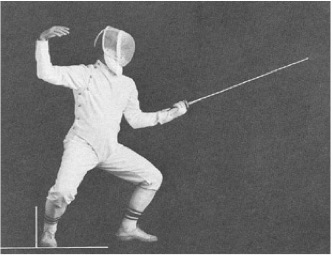

A very long time ago, I learned to fence. What you see above is a lunge. A lunge moves you from a defensive posture to an attacking one—you're trying to stab the other person. But notice that the figure is balanced. Its center of gravity is between its feet, and it could remain in that position without tipping either forward or back. If its opponent counters the attack and launches a counterattack, it could recover backward by pushing off the front leg, snapping the back arm up, and reassuming the original en garde position:

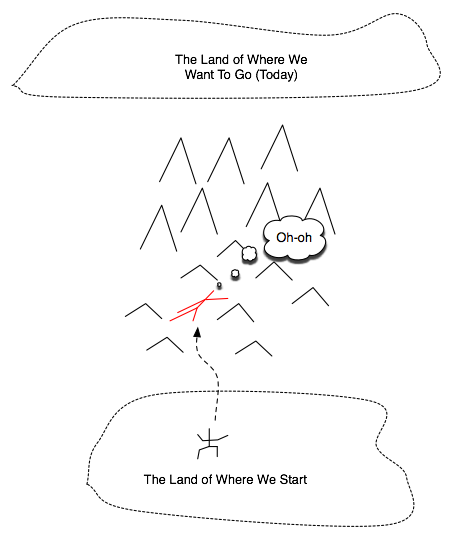

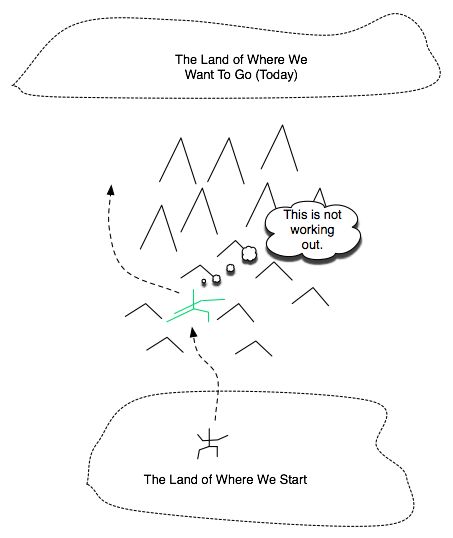

But suppose the opponent retreats away from the attack. Then our lunging figure can recover forward: keeping the center of gravity as is, pull the back leg in and curl the back arm. Now it's ready to keep pressing the attack: it can lunge again or move forward in a more guarded way. The important thing here is that—despite the failure of the original attack—the manner in which it moved forward allows it to keep moving forward. Software teams often seem to be unable to recover forward. If they make a wrong decision, they land off balance:

The can

scramble awkwardly backward (

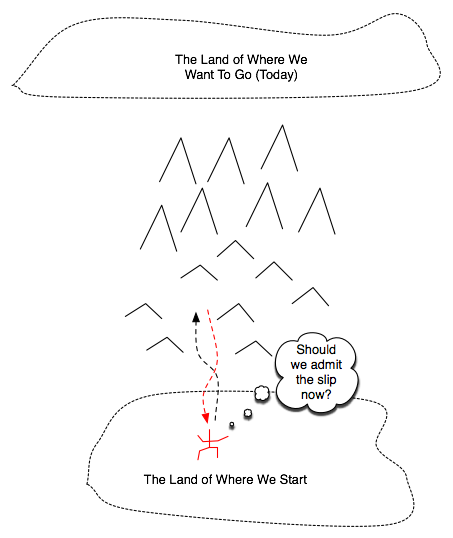

Or they can bull forward along a path they would not have chosen, had they known then what they know now, jabbing repeatedly and getting more and more off balance:

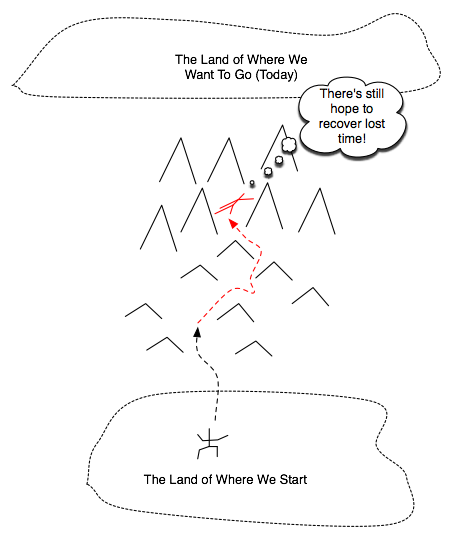

What they're unable to do is make use of where they are to take what now appears to be the best path:

For those of us who are merely mortal, it seems the best way to be able to recover forward is to practice the right stance. Get yourself into lots of situations where you end up going down the wrong path. Instead of reverting backward to a known stable state of code, add and rearrange code to move forward. A good way to get yourself into those situations is by only writing the code that's needed for the small feature you're working on right now. Then some later small feature will make you recover forward—and learn about how your stance is imbalanced. Some people believe you can recover forward from pretty much anything. (Ron Jeffries' Extreme Programming Adventures in C# demonstrates recovering forward from a design that doesn't support undo to one that does.) Others don't. I don't know what my opinion is, but I believe most people could recover forward a lot more than they think they can, if they practice. The trick is persuading them to practice. Credits: I learned to move forward instead of revert from Zhon Johansen. The first photo is from Dr. Stephan Dann and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license. The second photo is from http://www.tcnj.edu/~fencing/glossary.htm; there's no copyright notice, but it looks to be from an old fencing book.

## Posted at 14:05 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Sat, 17 Feb 2007Chet's idea - training for charity At SDTconf, there was a session on how to improve skills. It is too easy for people to come into a job not knowing enough and then get stuck at that level. Perhaps they deserve being stuck; perhaps they should be studying on their own. Nevertheless, they aren't, and their lack of skill sometimes (often?) prevents really successful Agile projects from forming. What to do, given that your typical 2-3 day course delivers some knowledge and some motivation, but not skill? Chet Hendrickson had an idea. This is how I remember it:

I'd like to be involved in this, but I don't see myself starting it up.

## Posted at 05:24 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Fri, 16 Feb 2007Is "impediment" an impediment? Descriptions of standups usually include the three questions, the last of which is something like "Are there any impediments in your way?" Listening to a standup a couple of days ago, I realized I've been hearing a pattern for years without paying attention: "... No impediments." I realized that "impediment" was being interpreted as something outside the team. But the metaphor of "impediment in your way" doesn't really work. The thing that's most often in my way is me: I don't know something, I'm thrashing around compulsively, etc. I wonder if the word "impediment" is making people less likely to say what really needs to be said: "I can't do this alone. I need help." (Random tip: when working with teams new to standups, I often take the most looked-up-to person aside and urge her to be the one to ask for help, hoping that will give other, less confident people the courage to be vulnerable.)

## Posted at 19:06 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Tue, 13 Feb 2007It seems to me that standups are often about what people did and are doing. They're like little slices of people's lives. Shouldn't they be more about the stories from this iteration? About how stories are progressing toward becoming complete? Holding standups in front of a story wall helps. People tend to gesture at the stories while they speak, making them the focus of attention. I was wondering today what it would be like if people pretended it were the stories themselves speaking:

That's too silly, except maybe for teams neophilic enough not to need it. I don't think I have the nerve to recommend it.

## Posted at 20:47 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Wed, 07 Feb 2007I often find myself coaching product directors in how to break up features into bite-sized stories. Usually we take one of their features and break it up. Here is an example of doing that. It shows the stories, the kind of explanatory sketches I'd expect to see on a whiteboard, and commentary. May it be of use to your product director.

## Posted at 12:39 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Tue, 06 Feb 2007Shifting work to the product director I realized recently that we on the development side of the Agile house have shifted work onto the already-overworked product director. Once upon a time, the business gave the development team a big chunk of work to do. They also asked the team to estimate the work. The team's estimates were almost always wildly wrong. Badness. A solution appeared: break the chunk down into small stories. (I like them to be half a day to three ideal days long.) Not only will the individual estimates be off by a smaller percentage, a sort of law of large numbers will cause the errors to average out, making the estimate for a whole iteration accurate. That's good for estimation, but programmers tend to think of system building as getting the infrastructure right and then popping features onto it. You can't take three weeks—or months—to build infrastructure if you have to finish the story in three days. So programmers wonder why the result of small stories isn't a big, unwieldy pile of disconnected code. I answer that there are tricks and tools to help: refactoring, the removal of duplication, IDEs that make large renamings and restructurings safe, reduction of code ownership, and so on. It is possible, I say, for the end result of small-story development to be a system that looks as if it had had an infrastructure designed in from the start. Swell. But something's been lost. In the old days, it was (somewhat) easy for the business representatives to wrap their heads around the release. They could talk about it as a large conceptual piece that hung together from the point of view of an end user. To some extent, the programmers were responsible for living up to that conceptual vision. Now, they no longer are. It's the product director who must keep track of all the small pieces and make sure they add up. Moreover, she must do that not all at once, but continually as the product grows throughout a release cycle. I think that's hard. The tools and tricks for doing it are not nearly so developed as are refactoring, etc. (There are some, such as Jeff Patton's span planning and feature thinning.) So we on the development side have made our estimation job easier by shifting work onto the business. Nice trick.

## Posted at 09:24 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Thu, 01 Feb 2007I'm flying back from Portland (a wonderful city), Agile Open Northwest (successful beyond expectation), and an Agile Alliance board meeting. Before the latter, we were given an assignment. We were to imagine ourselves on stage, opening the Agile 2012 conference. What would we say? I'd just bought a USB microphone, so I decided to record my imaginary speech, editing in sound effects and musical accompaniment. It's amateurish (the early clips go on too long), but you might be interested in it if you're interested in my take on the current state of Agile and the future I prefer. Until the 3:10 mark, it's all history. I talk about the current state until 4:45, after which I imagine the future. Most of the clips are before 4:45. Total length is just over 11 minutes. Credits: Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, James Brown, Patti Smith, the Sugar Beats, Elmore James, Pink Floyd, and Linton Kwesi Johnson.

## Posted at 22:26 in category /agile

[permalink]

[top]

Wed, 01 Nov 2006

My job is to give a thoughtful reaction to this essay, to describe what it means to a person with my perspective. Here goes.

We're not the first people in this situation—many have been in far worse—and as I reread Mr. Waldo's essay one day, I thought it might be instructive to see how those others have handled it.

One response, the default perhaps, is despair and retreat from engagement. I think we're all familiar with that feeling, and with those who've succumbed to it, so I won't discuss it further. The next two responses come from the Hellenistic period of Greek history, which followed the Classical period and was a time of turmoil, during which you might easily and uncontrollably go from great wealth to poverty or from power to slavery. This raised the practical question: how do you make yourself happy in a hostile world?

The wise person—the happy person—makes decisions based on how they align with the genuinely good. The results of those decisions have nothing to do with happiness: the Stoic would prefer they lead to wealth, health, and life, but is ultimately indifferent if they lead instead to poverty, sickness, and death. Epictetus puts it this way: Our opinions are up to us, and our impulses, desires, aversions--in short, whatever is our doing. Our bodies are not up to us, nor our possessions, our reputations, or our public offices... if you think that [those] things ... are your own, you will be thwarted, miserable, and upset, and will blame both the gods and men. From this, we get the popular image of the Stoic as someone who does what's right, because it's right, and is immune to attempts to sway her through non-rational emotions like fear of death. Marcus Aurelius, a later Stoic, put it this way: Say to yourself in the early morning: I shall meet today ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, uncharitable men... I can [not] be harmed by any of them, for no man will involve me in wrong. The Stoic approach to our problem would be to do thoughtful design because it is a good, and to be indifferent to the consequences. We would, for example, not care if the only company that would allow us to design well pays poorly, builds mundane software, and has no free soda in the kitchen. Stoicism is, I believe, what Mr. Waldo advocates. But Stoicism was not the only philosophy that sprang from the chaos of the Hellenistic period. Epicurianism was another.

The best strategy toward happiness is to pare your desires down to the minimum, which are then easily satisfied. One should avoid desires that are inherently unlimited, such as those for wealth, power, fame, and the like, in favor of desires that can be readily satisfied—by, say, filling your stomach when hungry. Moreover, simple food is easier to obtain than fancy food and fills the stomach just as well; therefore, you should strive to be happy with simple food, though equally happy to eat fine food when it's there. When I think of Epicurianism today, I think of the open source programmer who comes home from an unsatisfying job and spends part of the evening working on Firefox plugins or Ruby packages, designing them to meet the highest standards. Since, to Epicurus, current pain is outweighed by the mental pleasure of remembering past pleasures and anticipating future ones, the next day at work is thus made tolerable. A third reaction is, to a Western audience, most associated with the period after the stability of the Roman empire collapsed. It is a negotiated retreat from the field of battle.

Monasteries had defenses because they were liable to attack. Many of the attacks were like those of the Vikings on England, Ireland, Scotland, and elsewhere. Those attacks came from outside the existing, fragile social order. But there were also attacks from closer to home. A record that spans the 1400s shows that monasteries in Ireland had troubles long after the Vikings ceased to be a threat:

Still, the monks did not simply disappear from society behind walls. They provided value to those they'd left behind. For example, they would pray for the souls of your departed relatives.

And, of course, in Belgium there was beer. I am sure these services gained them some protection. When I think of monasticism today, I think of Agile projects. In Agile projects that are running well, there is an implicit or explicit deal between the team and the business. The team promises to deliver shippable business value at frequent intervals and not to whine when the business changes its mind about what it wants. In return, the business leaves the team alone to build the product as they like. That allows people who crave good design to do it—provided they can mesh it with the need to deliver frequently. In practice, that means that code becomes the whiteboard on which the design is discussed, rediscussed, and refined. This—in the best cases—seems to me exactly the same process Mr. Waldo describes. By that, I mean that the attitudes of people toward the design are the same, the conversations have the same air, the values informing the conversations are the same, and the code—in roughly the same time frame—comes to have as satisfying a design. I claim the monasticism of the Agile project is a more sustainable model than Stoicism or Epicurianism. It requires less of us because we get to lean on each other. Even programmers, notoriously not team players, gain strength from each other. Perhaps that's a claim we can discuss. For my part, I've recently become obsessed with the weakness of Agile Monasticism. Here is a story I heard from an ex-employee of a company I'll call Frex: [That] year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of [Frex], terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. [By this, he refers to the acquisition of Frex by a larger company.] These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine [the new head of marketing moved the Customer out of the project team room] and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men [a new VP of Development] made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island by rapine and slaughter. [The imposition of a "more mature" development process caused all but one of the team to quit.] Such stories are common. Agile projects have no real defensive walls; all they can do is deliver return on investment and hope the business values it. But we all know that ROI is only a part of what moves businesses. Those in the Agile world all know of resistance to Agile from those middle managers who see it as a threat to their power to command and control. Telling such a person that her sabotage endangers the company's ROI is like an abbot standing in the path of Christian raiders and threatening them with loss of their immortal souls: sometimes it works, but nowhere near often enough. And it never works with the worshippers of Odin.

This is—I repeat—still better than before. Teams do tend to protect their members. Testers are less likely to be offshored. Those who obsess about design can do it without justifying themselves to the unsympathetic. But the teams themselves, as wholes, have no structure of protection.

Mr. Waldo's essay, paradoxically, is leading me to seek answers to the

current problems of Agility in collective action exactly because its

focus on individual courage calls attention to our biggest blind spot:

we believe that each of us must alone contend against aggregates

possessing decades of institutional power. We don't even think about

standing shoulder to shoulder.

What path we should take, I don't know. Unionism is so foreign to the professional class in the US that I'm nervous about admitting I've ever even had the word in my mind. The ACM appears to me an organization for extracting money from people in return for papers printed in 9-point type, papers placed in bibliographic categories that don't seem to have changed since the seventies. Neither it, nor the IEEE, have enough spunk. The Agile Alliance, on whose board I sit, doesn't seem to have the right leverage. So I don't know what we should do, together, but I'll be thinking on the problem, and that's because of On System Design. Credits Special thanks to Donnchadh Ó Donnabháin, who tutoried me in Gaelic pronunciation. The photo of Despair is copyright by Carl Robert Blesius and was retrieved from http://blesius.org/gallery/photo?photo_id=1061. It is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 1.0 license. The monastery is used by permission of historylink101.net and was found at the Greek Picture Gallery. The fish picture is copyright by Toni Lucatorto and was retrieved from http://flickr.com/photos/toniluca/61782380/. It is distributed under the Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial 2.0 license. The picture of the dinosaurs is used by permission of clipart.com. The other photographs did not have copyright notices. |

|